Ooh, ooh, ooh, so much to tell. First of all, just want to thank you all who have been leaving comments--I am much more inspired to write when I know people are reading and plus, it makes me feel connected despite the thousands of miles. Also, if you are interested in seeing more pictures, click on the link to the left that says "More Photos." I will continue to include a few within each post and then upload the rest to my Picasa photo page (which is where that link will take you).

Ooh, ooh, ooh, so much to tell. First of all, just want to thank you all who have been leaving comments--I am much more inspired to write when I know people are reading and plus, it makes me feel connected despite the thousands of miles. Also, if you are interested in seeing more pictures, click on the link to the left that says "More Photos." I will continue to include a few within each post and then upload the rest to my Picasa photo page (which is where that link will take you).The last two days have been pretty great. Yesterday was spent almost entirely indoors, but luckily our classroom is airy and well-lit, thanks to door-length windows, which also provide a lovely view of the hills surrounding the IPE campus. Also lucky was the fact that class was particularly interesting yesterday--it focussed on climate change and the idea of an "ecological footprint," which is a metaphorical way to quantify how much the human species consumes of the world's natural resources. The smaller the footprint, the healthier the environment, the less destructive climate change.

You can calculate your own individual ecological footprint (or that of your household's) on this website. After taking a fairly involved quiz that asks you things like how many miles you drive a year and where you buy your food, you learn how many earths would be needed to sustain the human population if all humans lived the same way you do. If everyone lived like I do, we would need 3.6 earths. Sounds high I know, but the class's results ranged from 7 earths to 2.9, so I was actually on the lower end of the scale. I am curious to know what my parents would get--all that composting and Goodwill shopping has to be good for something! I encourage anyone reading to take the quiz and post your results in the comment section--I find it really fascinating and would love to know what you get.

Later, after another gorgeous sunset (I almost didn't even put a picture up because it does NO justice), we met individually with our professor, Tim, and our three TAs--Kaitlyn, who is from the U.S. and just completed her Masters in conservation at Columbia, and Fernando and Juliana, who are Brazilian. Fernando studies ocelots and jaguars, as well as a variety of monkeys. We discussed our individual projects. I had wanted to do something with edible vegetation, because I assumed that people who live on the edges of such a rich forest would forage in some manner, whether for medicinal herbs, mushroom, or fruit. Apparently, they don't. They do grow herbs and fruit, but in gardens, and they don't hunt for mushrooms like they do in the U.S. and Europe. They suggested instead that I do something involving ponds, which I find vaguely interesting--a comparison of the biodiversity (a word we use a LOT here) of several ponds in the area, for example. Tomorrow is our day to explore on our own and try to narrow down our focus, so we'll have to see what I find.

Later, after another gorgeous sunset (I almost didn't even put a picture up because it does NO justice), we met individually with our professor, Tim, and our three TAs--Kaitlyn, who is from the U.S. and just completed her Masters in conservation at Columbia, and Fernando and Juliana, who are Brazilian. Fernando studies ocelots and jaguars, as well as a variety of monkeys. We discussed our individual projects. I had wanted to do something with edible vegetation, because I assumed that people who live on the edges of such a rich forest would forage in some manner, whether for medicinal herbs, mushroom, or fruit. Apparently, they don't. They do grow herbs and fruit, but in gardens, and they don't hunt for mushrooms like they do in the U.S. and Europe. They suggested instead that I do something involving ponds, which I find vaguely interesting--a comparison of the biodiversity (a word we use a LOT here) of several ponds in the area, for example. Tomorrow is our day to explore on our own and try to narrow down our focus, so we'll have to see what I find. Today was split between the classroom and the field. The subject was abiotic--meaning non-living--components of the environment. We set up camp in a small pasture-valley bordered by the forest, broke up into groups and compared things like air temperature, humidity, light, and soil pH at different along four 150-meter transects that ran from the pasture into the forest--two along each of the two slopes of the valley. Basically, we wanted to know how different conditions were in the pasture and in the forest, as well as on either slope of the valley. We collected data and then brought it back to the classroom where we struggled (most of us are not science and math people; this program is an easy and exciting way to fulfill Columbia's 6-credit science requirement) with statistics in an attempt to make sense of what we'd found.

Today was split between the classroom and the field. The subject was abiotic--meaning non-living--components of the environment. We set up camp in a small pasture-valley bordered by the forest, broke up into groups and compared things like air temperature, humidity, light, and soil pH at different along four 150-meter transects that ran from the pasture into the forest--two along each of the two slopes of the valley. Basically, we wanted to know how different conditions were in the pasture and in the forest, as well as on either slope of the valley. We collected data and then brought it back to the classroom where we struggled (most of us are not science and math people; this program is an easy and exciting way to fulfill Columbia's 6-credit science requirement) with statistics in an attempt to make sense of what we'd found. What I found most interesting was the fact that the soil in the open, sunny pasture held more moisture than that in the dense, covered forest. The explanation for this is two-fold. For one, the forest has significantly more vegetation, or biomass, and plants suck up a lot of water. Two, the pasture collects dew every morning. Tricky. Another cool thing I learned is called Humboldt's rule. [Disclaimer: this might put you to sleep.] Scientists have determined, as a general trend, that for every 1000 meters that you go up in altitude, there is a decrease in temperature of about 6 ° C and concurrently observable changes in plant life. That decrease and those changes are equivalent to what you would see if you were to move latitudinally a linear distance of 500 to 750 km at the same elevation. In other words, hiking up 1000 meters is the same as walking 500 to 750 flat kilometers in terms of how much the environment around you changes.

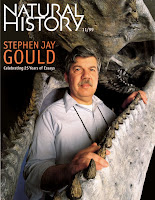

What I found most interesting was the fact that the soil in the open, sunny pasture held more moisture than that in the dense, covered forest. The explanation for this is two-fold. For one, the forest has significantly more vegetation, or biomass, and plants suck up a lot of water. Two, the pasture collects dew every morning. Tricky. Another cool thing I learned is called Humboldt's rule. [Disclaimer: this might put you to sleep.] Scientists have determined, as a general trend, that for every 1000 meters that you go up in altitude, there is a decrease in temperature of about 6 ° C and concurrently observable changes in plant life. That decrease and those changes are equivalent to what you would see if you were to move latitudinally a linear distance of 500 to 750 km at the same elevation. In other words, hiking up 1000 meters is the same as walking 500 to 750 flat kilometers in terms of how much the environment around you changes. Did that make sense? I find it so frustrating that it is incredibly difficult to write well about science. There are so few people who can explain things thoroughly and clearly, not to mention do so in finely-wrought prose. This guy is one of them, and it was a beautiful essay of his assigned in my first human evolution class that inspired me--and JD, if I remember correctly!--to study biological anthropology. For many years, beginning when I was 10, I wanted to be a food critic. But now that food writing has become such a massive and popular industry, I feel like my talents (how modest) might be better put to use improving the underdeveloped field of science writing.

Did that make sense? I find it so frustrating that it is incredibly difficult to write well about science. There are so few people who can explain things thoroughly and clearly, not to mention do so in finely-wrought prose. This guy is one of them, and it was a beautiful essay of his assigned in my first human evolution class that inspired me--and JD, if I remember correctly!--to study biological anthropology. For many years, beginning when I was 10, I wanted to be a food critic. But now that food writing has become such a massive and popular industry, I feel like my talents (how modest) might be better put to use improving the underdeveloped field of science writing.Someone told me that a girl who went on this program last year lost 30 lbs by the time it was through. I was delighted by this news until I realized that I've been eating about 30 lbs a day. Sure, I am tromping around the forest, but I don't think I'm burning quite enough calories to cancel out the effects of the three enormous meals, plus frequent coffee breaks (with cake or cookies) and occasional Clif bar, that I consume a day. If you'd like to read more specific accounts of what I'm wolfing down, look no farther than food game, a blog that Brie Kluytenaar (sister of Van) recently started. Contributors to this blog (which include myself, known as "H," Van, his other sister Tara, and good old Dan Shapiro--what up, Beaver Hill!) post specific, descriptive lists of their daily meals. Some find this bizarre, but for me, who insists that everyone she knows tells her exactly what they ate at an interesting restaurant or what they cooked last night for dinner, it is like food pornography.

In biotic (living organisms) news: I take back what I said about the forest looking similar to those of the Northeast United States. I say this perhaps because my eye is a bit better-trained and because there are vines (lianas) everywhere and because I have seen some freaky plants. Plus, I saw another sloth! The problem with non-predatory forest mammals is that to protect themselves, they live very high up in the trees. Great for their survival, but they're very difficult to see without binoculars, and even then, all the leafy branches get in the way. I could only crane my neck for so long but I did catch a few glimpses of her sluggish body (did you know that sometimes it takes so long for a sloth to reach a food source that it STARVES on the way? absurd!). I know it was a her because she had a cub with her! Unless it was a really great single dad-sloth--unlikely. Unfortunately, I did not actually see the cub, but sighting of a smaller arm clutching the adult were reported. I did see some dainty butterflies (that's my arm pictured) and I took charge (and pictures) of an empty hummingbird nest that TA Fernando found on the forest floor.

In biotic (living organisms) news: I take back what I said about the forest looking similar to those of the Northeast United States. I say this perhaps because my eye is a bit better-trained and because there are vines (lianas) everywhere and because I have seen some freaky plants. Plus, I saw another sloth! The problem with non-predatory forest mammals is that to protect themselves, they live very high up in the trees. Great for their survival, but they're very difficult to see without binoculars, and even then, all the leafy branches get in the way. I could only crane my neck for so long but I did catch a few glimpses of her sluggish body (did you know that sometimes it takes so long for a sloth to reach a food source that it STARVES on the way? absurd!). I know it was a her because she had a cub with her! Unless it was a really great single dad-sloth--unlikely. Unfortunately, I did not actually see the cub, but sighting of a smaller arm clutching the adult were reported. I did see some dainty butterflies (that's my arm pictured) and I took charge (and pictures) of an empty hummingbird nest that TA Fernando found on the forest floor.I am hoping my entries will become more precise and thus concise as I get used to writing them, but until then, thanks for reading! It is 7 pm, time for jantar (aka dinner). Can't wait to find out what's on the menu. At 8:30 begins our social--we found out this morning that they're bringing in a Samba band! Looking forward to some cringeworthy scientist-dancing....

10 comments:

5.05 earths for us but I might have over estimated the miles we drive each year - we were low on the carbon footprint and the goods and service and right-on the national average on the other 2 categories - food and household - you were probably so low because you don't drive a car or have a house, which are good things - love you, Mom

having fun and learning too - what could be better? how are the hking boots working out? that guy Gould died so young! love you, Mom

get someone to take your picture so we can SEE how happy you are - OK, enough from me for today - love you lots, Mom

P.S. can someone tell me how my being able decifer the letters below this comment field constitutes a security measure?

H!

you are my daily read, so much more better and interesting than what passes for news from the media

maybe you could do some work on why people who live near the forest don't forage - ?

g - the transcription of images that look like letters is a human-only challenge; the netbots (tools of Internet comment-spammers) cannot accomplish this so it keeps them out, a good thing

3.26 earths for us

for dry air, there is this thing called the dry adiabatic lapse rate. basically, anytime a parcel of dry air rises in the atmosphere, it expands and cools. thermodynamics has a couple equations that describe this kind of cooling. if you use them to solve for the change in temperature with respect to elevation for dry air, you get something like 9.8 degrees C per 1000 m of height.

the reason Humboldt's rule works is because most air has a certain about of water in it (1-4% by mass usually). water has a higher heat capacity (it takes more energy to change the temperature of water), so the temperature of wet air is less sensitive to elevation. that's why you observe something like 6 degrees C per 1000 m. if the air is very cold (and therefore has much less water in it), the lapse rate is much closer to 9.8 degrees C per 1000 m.

check it out on wikipedia. dry adiabatic lapse rate.

sounds like you are doing cool stuff =)

tks

oh, just a minor nitpick.

when you say moving vertically 1 km is about equal to 500-750 m over land with respect to observed plant life, i think it has to be 500-750 m due north or south, depending on your hemisphere. or maybe you said latitudinally and i missed it.

can you bring me back a monkey?

tks

i did say latitudinally, but thanks for caring! i already picked out your monkey--his name is TKMC and he is cuuuh-YUTE!

We will calculate later, but meanwhile, I LOVE the photo section (and thanks for the primates).

It all sounds fascinating (especially the parts I don't

understand...). So glad you're thriving there!

And: how about one of those corny, "here I am in our

room (in the rain forest, by the lake, whatever) with

my roommate" photos?

Love you lots,

Laurie, Euge, Clara, Mango

But now that food writing has become such a massive and popular industry, I feel like my talents (how modest) might be better put to use improving the underdeveloped field of science writing.

How about a Cook's Magazine/Science hybrid? I'd be down for that.

Post a Comment